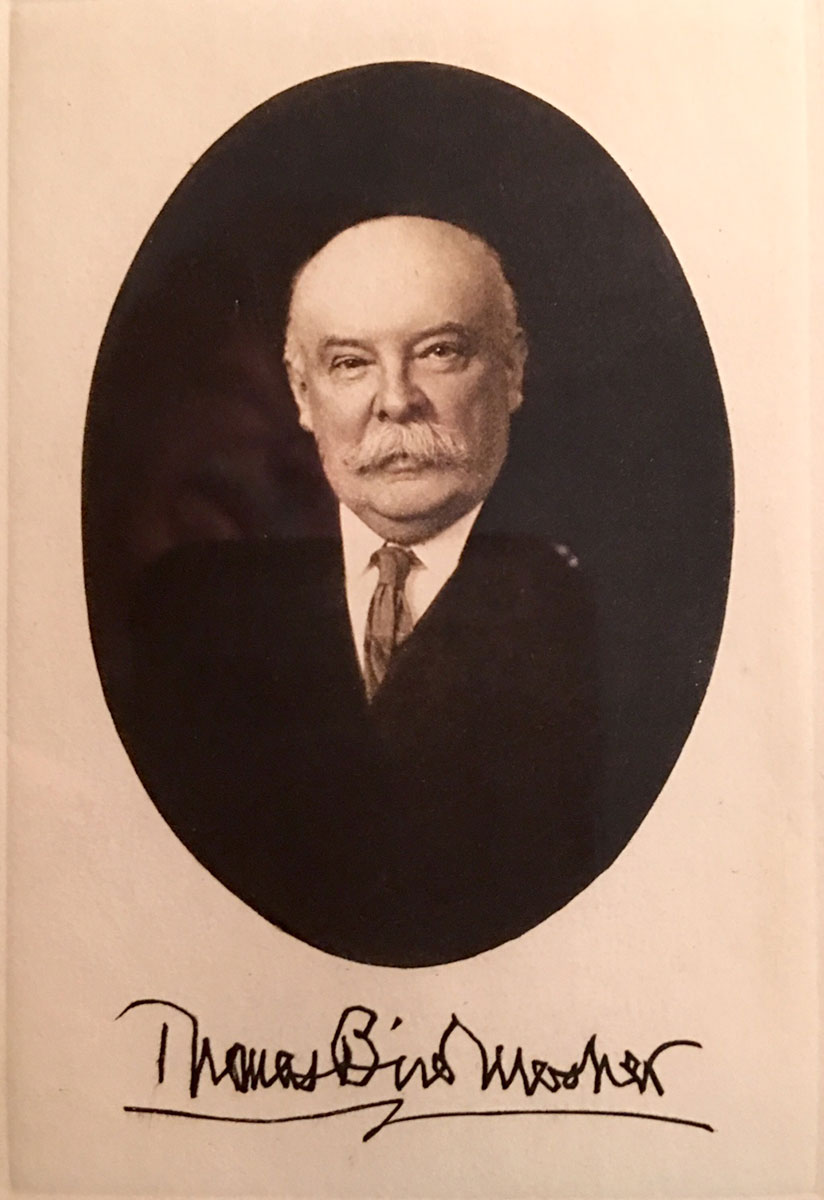

Thomas Bird Mosher

1852-1923

Passionate Pirate and Prince of Publishers

The bow plows through heavy seas as Captain Benjamin Mosher’s merchant clipper ship, Nor’wester, rounds Cape Horn on its fourth passage through the torturous Strait of Magellan with his family aboard. A precocious fourteen-year- old steadies his chair in the captain’s quarters while reading from a multi-volume, 18th century set of Bell’s British Theatre, a gift from the skipper –his father– in 1866. As Thomas Bird Mosher would wistfully reflect in his 1912 catalogue:

No! I shall never again read books as I once read them in my early seafaring when all the world and love were young! Nor shall I forget those days of tropic splendor, or nights when only a faint and oily lamp swung in the lonely cabin; the plunging ship midst ocean’s grey and solitary waste, and the long wintry passage around Cape Horn.

This was the beginning of a love for literature and its interpretation of life that would inspire Mosher throughout his career. And it’s one of the many fascinating stories surrounding America’s fine-press publisher that would prompt the poet Robert Frost to remark that Mosher stirred a biographical impulse in him. Mosher’s publications would eventually become well known in San Francisco, Sydney, Bombay, London– wherever English was spoken. But first he had some dues to pay.

A lad who experienced such a sea adventure could hardly be expected to buckle down upon return to a mundane life in Maine. This isn’t a story of instant success, however. In fact, following Mosher’s return to Maine in 1870 we find a trail of losses, failures and fumbled attempts, the hard knocks of life that either break us or steel-harden us for the road ahead. He never was able to complete any formal schooling beyond the Quincey Grammar School in Boston (Christopher Morley once noted, he was “an uneducated man, as uneducated as Chaucer and Lamb and Conrad”). On December 10, 1870, he secretly married a local girl, Ellie Dresser — and like a thief, would climb the arbor of her parent’s house each night to be with his bride. But he got caught in her bedroom to the immense consternation of both families, who demanded formal marriage. The couple was publicly remarried on July 4, 1871.

Following his marriage, Mosher’s father forced him out on his own and he worked at several dead-end jobs in Portland, Maine, and in St. Louis and Philadelphia. Then, between 1879 and 1885, came a series of blows: his wife divorced him and moved to New York City, his dearest friend, Leopold Lobsitz, died suddenly while at Harvard Medical School, and his father also died. In 1889 his attempt at some sort of job stability, a partnership in a Portland law-book and stationery business, ended when the business went bankrupt.

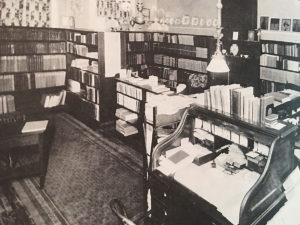

But Mosher was nothing if not tenacious. He re-opened the stationery business as a wholesale operation with himself as sole proprietor. It was during this period, as he produced state reports and ledgers, the paraphernalia of government and commerce, that Mosher accumulated the practical knowledge that a bookman needs. He found sources for paper and other book materials, he devoured manuals on typography in the way only an autodidact does, and he established working relationships with printers and binders. All the while Mosher quietly collected books and literary journals, and began to build his library. Given his passion for books, Mosher’s next step was inevitable.

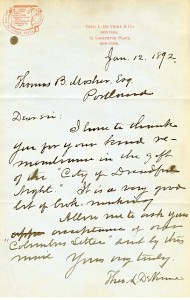

In 1891 Mosher took that step and published Modern Love (see reviews), by George Meredith. A curious choice, but the poem seemed to reflect his own romantic tribulations, and he forever loved to quote the poem’s last line, “To throw that faint thin line upon the shore!” For Mosher, that thin line was a metaphor that encapsulated his efforts to introduce the literate but largely unread public to the delights of finer literature. He wanted to guide their way, to help them gain a mooring in this high art. He published James Thompson’s The City of Dreadful Night shortly thereafter in 1892, and he brought out his first anthology, Songs of Adieu, in1893. It was to be the initial volume of The Bibelot Series.

Between 1891 and 1895, even while attending to his stationery business, Mosher managed to publish sixteen books. He decided to sell his stationery business, and he started what would eventually become one of his most famous publications –-the little literary periodical called The Bibelot. He also sent out his first major catalogue to what was now an admiring public.

What motivated Mosher to a full-time career as a publisher? Several reasons may be offered in addition to his passion for book collecting and his success as a stationer. Mosher had a ready model in the private press movement in England, which had drawn his attention. Publications like The Century Guild’s The Hobby Horse (printed by the Chiswick Press), productions from the newly formed presses like the Kelmscott, Eragny, Doves presses, and the products of The Bodley Head in England–all showed that texts Mosher considered important could also be delightfully printed in beautiful formats. Choice paper, clear typography, and selective use of graphic design could be thoughtfully combined to make a well-integrated book. The common Victorian book was anything but well-integrated. One only needs to see its mishmash of poor paper, jumbled typography, and unsatisfactory plain or heavily stamped bindings, to appreciate how radically different the private press productions really were, and how little this art was being practiced in America (the work of DeVinne, Gilliss, and even H. O. Houghton were notable exceptions). Another reason was that Mosher truly believed for himself, and for others, that life’s tragedy and justification could be discovered through literature. These, coupled with the gradual sales success of those early trial publications, all combined to provide a new raison-d’être for Mosher’s life.

The American book designer, Bruce Rogers, once referred to Mosher as the “Aldus of the Nineteenth Century,” explaining in a 1909 letter to Mosher (now at the Houghton Library):

I did mean the reference to Aldus seriously—for you have (to the despair of us all) succeeded in doing just what he did 400 years ago, almost to a year, i.e., making beautiful little editions of the best writers in inexpensive form. The last is the most annoying feature of it all—and how you do it I can’t see—unless, indeed, you pocket the loss—which I don’t believe.

Indeed, like Aldus Manutius, the 15th-century printer of Venice, Mosher began his publishing career rather late in life at age 39. And like Aldus —who first used the anchor- and-dolphin printer’s device, which Mosher too would incorporate into his publications— he provided a steady stream of finely printed books for the masses, at affordable prices. That first book in 1891 heralded a flow of limited editions that would reach a total of 730 titles and editions by the end of his publishing career. People the world over would delight upon receiving the annual Mosher book catalogue, and orders for books as gifts would be especially strong during the holidays. After all, there was something unique in the way this man expressed himself. The introductions to Mosher’s catalogues were personal and captivating, almost like one soul speaking directly and profoundly to another. Richard LeGallienne described them as “the catalogue raisonné lifted into the region of poetry,” and in The Haunted Bookshop, Christopher Morley wrote that he’ll take “some of Mr. Mosher’s catalogues: fine! they’ll show the true spirit of what one book-lover calls bibliobliss.”

Mosher had a knack for selling his books. One of his methods was to capitalize on controversy for free publicity. Mosher’s passion for literature could be easily gleaned from his catalogues, and in his introductions to issues of The Bibelot. This same passion led him to relentlessly pursue little-known texts and fine literature, and reprint them with or without the permission of their authors. A controversy between the Portland publisher and certain English authors and publishers first erupted in 1895, and then again just before World War I. The charge . . . literary piracy. It was the English author, Andrew Lang, who led a tirade of claims against Mosher. Charges and counter- charges were hurled between widely read literary periodicals, including The Critic. A sampling of these exchanges includes Lang stating:

I read in The Critic that a Mr. Mosher has published my ‘Aucassin’; apparently for his own emolument. May I ask Mr. Mosher if he ever requested my leave to reprint the book which had been bungled. If he was so discourteous as to crib my work, he gained nothing by his bad manners.

—Andrew Lang, Jan. 8, 1896

and later on Mosher returned the fire by taunting Lang::

I have to-day mailed you copies of my ‘Old World’ edition of your translation of ‘Aucassin and Nicolete.’ I have simply taken what I admired, and am, no doubt, no better than my brother pirates. If there was, as you assume, any discourtesy, I am sorry for it. I can assure you I should enjoy your work, though you cursed me with a twenty devil curse. But why not let your good humor prevail and ascribe the forcible entry to mere inability to keep my hands off your exquisite productions.

—T. B. Mosher, April 21, 1896

So Mosher became known as a literary pirate —some said a literary Robin Hood— and his books were banned from England. Raids were even made of some English bookstores and auction houses that tried to sell his wares. Luckily only a few of England’s authors and publishers took aim at Mosher. Others came to Mosher’s defense, and challenged their own publishers to bring out editions as beautiful and as affordable as were Mosher’s wares. They knew that he wasn’t technically breaking any of the laws under the 1891 International Copyright Law. They also knew that they were gaining an American audience they wouldn’t otherwise have had, and many an English author was pleased to see his work so beautifully printed, bound, and so widely distributed. In 1892, George Meredith, Mosher’s first “victim” wrote:

Sir, a handsome pirate is always half pardoned. And in this case he has broken only the upper laws. I shall receive with pleasure the copy of ‘Modern Love’ which you propose to send. I have it much at heart that works of mine should be read by Americans.

When Mosher traveled to England in 1901, he met many authors and publishers who had come to know the “Portland Pirate” through his reputation and personal correspondence. He even met his archenemy, Andrew Lang; it’s said they parted as friends.

Another tactic that clearly rewarded Mosher was to offer his book wares in fourteen different series. Generally speaking, a series promoted a particular literary theme, or style of imprint, and presented a concentrated area of collectability for the book lover. The implied message was to buy books leading to the completion of a series. You could select books from the English Reprint, Bibelot Series, Vest Pocket (literally slender enough to fit in a suit pocket), Lyric Garland, or the Golden Text series. Then there was the larger Quarto Series, the Ideal Series of Little Masterpieces, the Lyra Americana Series, Reprints of Privately Printed Books, the Old World Series, The Venetian, Reprints from The Bibelot, and the fanciful Brocade Series named after the brocade patterns covering the slipcases. The Miscellaneous Series was Mosher’s largest, numbering 98 titles, sizes and formats. Regular copies from the different series (limited from 400 to 925) were usually printed on Dutch Van Gelder, hand-made paper manufactured and imported from Holland. Most of his books were bound using either paper boards or paper wraps over flexible boards, usually employing some decoration on the cover, or using decorative papers to enhance their attractiveness. To further fuel the collecting urge of even more well-to-do buyers, Mosher would offer more highly limited and signed press runs printed on Japan vellum — a manila colored paper manufactured in Japan and made from the inner bark of shrubs distantly related to the mulberry tree. For the wealthiest of his clientèle, pure vellum copies were printed, but unadvertised. The pages of these delicate snow-white, pure vellum copies were manufactured from sheep or calf skin, and were limited from 4 to 10 copies per title. It is a little known fact that Mosher printed more titles on pure vellum (47) than any other publisher or printer in America for the comparable period (even the America bastion for the well-to-do collector, The Grolier Club, only published 30 titles on vellum between 1884 and1923!).

Mosher’s publishing program surged by the fin-de-siècle, and commissions were even being accepted for some “vanity press” publications. He boasted that 15,000 copies of just one little “Vest Pocket” Rubáiyát were sold in little over one year (the Vest Pocket books didn’t carry a limitation statement). An arbiter of literary taste in America, The Critic, announced that it “shall congratulate the first American poet who gets Mr. Mosher to introduce him to the public.” Many tried. Even the American poets Robert Frost and Ezra Pound courted Mosher to bring out their first books, but Mosher would never publish one word of Pound’s, and Frost could only get Mosher to publish his poem “Reluctance” in his 1913 catalogue. Mosher’s tastes lay with English literature, and though a few American poets would be so honored —including a great facsimile tribute to Walt Whitman— most of Mosher’s efforts would be to introduce the more exotic flowers of Western literature to Americans. He introduced the American public to the riches of the Irish Revival, to the English Aesthetes and Pre-Raphaelites, the French Symbolists, and to forgotten ancient and medieval texts which people like William Morris and Fiona Macleod were popularizing in England. In fact, Mosher brought out several of William Morris’s writings that appeared for the first time in book form, among them Gertha’s Lovers – A Tale (1899), and The Two Sides of the River and Other Poems (1899), both taken from the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine of 1856.

Mosher’s highly discriminating taste did more than provide exquisitely printed books for a wide middle class “republic of booklovers.” He cultivated connections and publications for the Omar “cult,” and for those associated with the Walt Whitman fellowships on both sides of the Atlantic. He prided himself in bringing out important editions of English literature, including the first facsimile of the then extremely popular Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the first reprint of the seminal Pre-Raphaelite publication, The Germ, and important compilations of poetical and other works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ernest Dowson, Walter Pater and A. C. Swinburne. He even boldly promoted the poetical works of Oscar Wilde when such allegiance was most unpopular following Wilde’s conviction for sexual perversion in 1895. And in 1919 Mosher brought out what some consider his tour de force, the first facsimile reprint of one of the most important poetical texts of the modern era, Walt Whitman’s 1855 Leaves of Grass. It was the publisher’s personal tribute to commemorate Whitman’s 100th birthday anniversary. Then, as one of his last books to be published, Mosher enticed Bertrand Russell to endorse a reprint of the remarkable little work, A Free Man’s Worship, which Mosher claimed was the last word on the subject of man and the universe. Russell was pleased with the result, which included a fresh introduction written by the English philosopher himself. This was the first time this work ever appeared in book form.

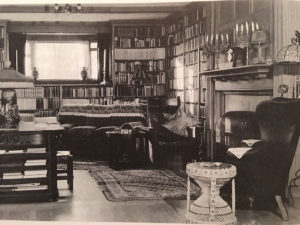

Mosher’s fame and publications brought him many friendships, and his publication program and book sales often drew support from these individuals. Robert Frost counted him as friend, as did the author Richard LeGallienne, who even wrote and published a touching tribute to Mosher, a small portion of which here epitomizes the extent to which Mosher- the-collector turned his library into something else:

Taste actively employed must result in some form of personal rearrangement of its objects which gives one the sense of a new Harmony. Thus an individually selected library often becomes the artistic embodiment of its owner’s personality. A real book-lover, that is one whose books are each and all sensitively related to himself, is known by the books that he buys. His library is a microcosm of his individual cosmos. The catalogue of a man’s library is a form of autobiography. Now, this principle has been carried on step further in our own time by one who has shown us that not only the criticism and collection of books may belong to the creative arts, but the publication of them also.

–Thomas Bird Mosher—An Appreciation (1914)

Steady correspondence between English authors like Gordon Bottomley, E.V. Lucas, and George Russell (of the Irish Renaissance and Celtic literature movement), often kept Mosher informed of behind-the-scenes happenings in England’s literary world. American editors and publishers like William Marion Reedy of the St. Louis Mirror, W. Irving Way of the prestigious Chicago firm of Way & Williams, the New York publisher Mitchell Kennerley, Ralph Fletcher Seymour of the Alderbrink Press, and Walt Whitman disciple, Horace Traubel of The Conservator in Philadelphia, all saw in Mosher a special genius apart from any other publisher in the business. Mitchell Kennerley recollected that:

Mr. Mosher made popular in America such authors as Walter Pater, Andrew Lang, Arthur Symons, Maurice Hewlett and a host of others many years before they would have otherwise become known . . . there is no doubt that he did more for the cause of pure literature in America than any other publisher America ever had.

Admirers like actors Julia Marlowe, Ellen Terry and even the Barrymores looked up Mosher when they were in America. Some of New York City’s elite– for example, Henry William Poor (of Standard and Poor) and Emily Grigsby (heiress to the Yerkes fortune of Chicago)– not only got to know Mosher, but had some of his choicest limited editions specially bound. Strong and abiding relations were formed with members of America’s distinguished book circles of the day, especially within the premiere book club of America, The Grolier Club of New York, and within the American Omar Khayyám Society in Boston. Mosher would often meet with such “inner circle” book society, at whose functions he would enthusiastically demonstrate his Epicurean appreciation of fine foods and wine. But he didn’t ignore his regular customers either. It’s remarkable how much time he seemed to find to answer some personally addressed inquiry, or to explain some term or obscure fact to a purchaser of a Mosher book.

One of the more intriguing aspects of Mosher’s life was his relationship to his first wife. Mosher remarried ten years after his divorce. As previously noted, his first wife left him, moved to New York City, and then reportedly died. It was not known until rather recently that Ellie (Dresser) Mosher changed her name to Amiee Lenalie, and was actually introduced several years later by Mosher to two of his closest friends, the publishers William Marion Reedy and Mitchell Kennerley. Neither man knew of the former connection, and Lenalie worked for both, falling in love with the latter. We even find the name “A. Lenalie” as a translator of a couple of Mosher’ s books (Mimes and “R.L.S.” An Essay, both by Marcel Schwob). The secret was kept from almost everyone, including the second Mrs. Mosher. Visits were made to New York, and correspondence flowed freely between the two. Upon Mosher’s death, one of the first things his long-time assistant, Flora Lamb, did was to get the key to his office desk, take out all the letters sent from Lenalie over the years, and throw them into the burning fireplace. At least one card survives though, at The Houghton Library, where she writes to her former husband at the end of 1913: “Nöel 1913 New Year 1914. I have much joy of the unexpected remembrance from you — and for all the past, and the future that grows dim. I have always thought of you. May I pass on before you that I escape sorrow. A.L.” She didn’t get her wish. Mosher died on August 31, 1923. “Aimee Lenalie” died on October 5, 1924.

One of America’s leading printers of the day, Theodore DeVinne, praised Mosher’s early books as they first became known to the American public. Notes of acclaim were written on both sides of the Atlantic. Christopher Morley referred to Mosher as “the prince of editors,” and the firm of William Wise in New York called him America’s Prince of Publishers in its advertisements for the reprint of Mosher’s little periodical, The Bibelot. Modern assessments include a variety of appraisals, and just a few are here cited:

- Joseph Blumenthal, one of America’s distinguished typographers and owner of the Spiral Press, states that Mosher “is the first American to have established and sustained a program, over thirty-two years, of splendid literary output in consistently felicitous typographic form.” (The Printed Book in America, 1989)

- Susan Otis Thompson, who includes a chapter on Mosher in the newly republished American Book Design and William Morris, also writes: “His ability to combine the two enthusiasms [love of literature and fine printing] in a long series of titles published at modest prices is what makes him an enduring figure in the history of American bookmaking . . . Mosher had disseminated his books wider than any private press, while investing in them a degree of personal conviction no trade publisher could possibly emulate.” (The Art that is Life, 1987)

- The artist-illustrator, sculpture and printer, Leonard Baskin, notes that “he was influential & important on many different levels.” (The Gehenna Press-The Work of Fifty Years 1942-1992)

- John Bidwell, former curator of The Cary Collection at the Rochester Institute of Technology, wrote that “…what really what really distinguished Mosher from Stone & Kimball (or from any other of the new turn-of-the-century publishers for that matter) was a consistent and deliberate refinement in his choice of texts and typography. Above all else, Mosher was an admirer of good taste, and, having arrived at a precise, personal understanding of what it should be, he imposed it rigorously on every one of his books . . ..”(New York-Pennsylvania Collector, April 1978)

- Norman Strouse, one-time president of J. Walter Thompson Advertising, a long-time collector of Mosher, and writer of his only separately published biography, wrote: “Basic to the delight one experiences in handling Mosher books is the exquisite hand made paper on which he exercised his rare talent for book making. Although Mosher drew on sympathetic craftsmen to print his books, every volume spoke eloquently of a personal dedication to the concept of a private press. Mosher books were a simple extension of the personality of Thomas Bird Mosher and his compulsive delight in the spiritual treasures of literature . . . ” (The Passionate Pirate, 1964)

Mosher did stand apart on a loftier but secluded level from his fellow publishing brethren, and his passion for literature, combined with a keen aesthetic sense and aggressive business practices, afforded him the opportunity to bring the gems of literature to the common man in a way no other American publisher had before, or is ever likely to again. For those who turn to collecting Mosher’s books, the more they are assembled, examined, and at least spot-read, the closer the collector will come to understanding and appreciating the personality of a publisher whose force of spirit still resonates at the cusp of the 21st Century.

SIDE BAR #1

Mosher Collecting Highlights

The following books are some of the crème de la crème of any Mosher book collection. The prices given are for near fine to fine copies at prices I have sometimes seen on these books. Prices for Mosher books have never been stable, and what one dealer many have at $15, another will price at $65 (especially books from The Brocade Series). So the following should be considered as a guideline.

- George Meredith’s Modern Love (1891). Mosher’s first book. Small paper, $125-150. Large paper, $250-$300. Large paper on Japan vellum $500+

- Kelmscott look-a-likes: Rossetti’s Hand and Soul (1899), $150-250; Matthew Arnold’s Empedocles on Etna (1900), $125-225. Both books use Morrisian borders and capital letters. Have seen these go as high as $350. Japan vellum copies add another $100.

- Vale Press imitation, Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel (1901) with large, lead initials design by Charles Ricketts. $75-125. For Japan vellum add another $75-100.

- William Morris’s Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair (1900). One of Mosher’s larger sized reprints; opening page to Chapter One is striking. It’s actually the first American edition, albeit unauthorized. $150 or more. Japan vellum, $300

- A.E.’s (George Russell) Homeward: Songs by The Way (1895). Not only is this a first edition of many of George Russell’s poems, but is also one of the first books with Bruce Roger’s designs (famous American book designer), and the first book to carry his name in a colophon and his initials in a design. $150- $250. Japan vellum copies $350+

- Rossetti, et.al. The Germ (1898). This is the first reprint of the Pre-Raphaelite magazine, which today goes for $175-250. Japan vellum copies can command up to $350-400.

- A real sleeper is Swinburne’s A Year’s Letters (1901). It’s not only a first American, but it’s the first edition ever in book form. Regular copies go from $75-100. Japan vellum, $200+

- There are three lovely books with fine art nouveau covers, and fine copies will go for $85 or higher. They are: Fancy’s Following by Anodos, i.e., Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (1900); Fragilia Labilia by John Addington Symonds (1902); and Primavera: Poems by Four Authors (1900). Another very attractive volume is Mimes by Marcel Schwob (1901), translated by A. Lenalie, a pseudonym used by Mosher’s first wife. The attractive gold and violet cover is by American designer, Earl Stetson Crawford, and copies typically go for $50-75.

- Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1919) is certainly not the typical Mosher book, and it’s the first facsimile of the 1855 text ever printed, true to its predecessor right down to the remarkable green duplicate binding! Regular copies go for $150, and Japan vellum copies for $400+

- Edward Calvert’s Ten Spiritual Designs (1913) is one of Mosher’s largest books. Calvert was a student of William Blake, and the charming illustrations are in a special portfolio section. Price is around $375-$425. A related book is William Blake’s XVII Designs to Thornton’s Virgil (1899). These original woodcuts (only ones Blake ever did) are haunting and here reproduced en masse for the first time since their original appearance in 1821. Furthermore, the book contains early designs by Selwyn Image and Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, two early exponents of England’s Arts and Crafts Movement. Price is usually around $125-175. For Japan vellum copies, add another $100-150.

SIDE BAR #2

Sources for More Information

The following sources will provide more information on Mosher and The Mosher Press:

- Vilain, Jean-François and Philip R. Bishop. Thomas Bird Mosher and the Art of the Book. (Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co., 1992). Excellent 112-page exhibition catalogue with 71 b&w photo- illustrations. $24 plus shipping from most books-on-books dealers, or by calling 717-872-9209, or contact by eMail at

- Thompson, Susan Otis. American Book Design and William Morris. With a new foreword by Jean-François Vilain. (The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 1996). Hardcover $49.94, paperback $34.95. To order, dial 1-800-996-2556

- Strouse, Norman. The Passionate Pirate. (North Hills, PA: Bird & Bull Press, 1964). The only single biography in book form, now an expensive private press book priced at $650-$850.

- Hatch, Benton L. A Check List of the Publications of Thomas Bird Mosher of Portland Maine.. (Amherst, MA: Printed at the Gehenna Press for the University of Massachusetts Press, 1966). Another rare press book, prized as a Gehenna Press item, is usually priced at around $275-$350.

- A Web page is currently under construction for Thomas Bird Mosher and The Mosher Press. For this, and/or to be listed for notification when the new Mosher bibliography is published, send your eMail request to or call 717-872- 9209.

- Of course, there’s nothing better than to see the books for yourself. Major institutional collections are located at The Gleeson Library at the University of San Francisco; the Mudd Library at Yale, the Library at the University of South Florida, Bowdoin College Library, the Hayden Library at Arizona State University-Tempe, the University of Louisville Library, the Miller Library at Colby College, The Houghton Library, the Portland (ME) Public Library, and the Kalamazoo College Library, just to name a few.