Morley, Christopher. “A Golden String” in Amphora: A Second Collection. Portland, ME: Mosher, 1926, pp. 109-113. Reprinted from the Saturday Review of Literature in the July 11, 1925 issue on p. 892, and later published as “A Dogwood Tree” in Morley’s John Mistletoe. New York: Doubleday, 1931, pp. 316-321.

Here and there, leavened in among masses of populace, are those few to whom the name of the late Thomas Bird Mosher still carries a special vibration. Mr. Mosher spent more than thirty years in betrothing books and readers to one another; like the zooming bumble-bee and with a similar hum of ecstasy he sped from one mind to the next, setting the whole garden in a lively state of cross-fertilization.

The famous twenty volumes of the Bibelot are Mosher’s testament, both the greater and the less as his friend Villon would have said. These are twenty books–yes, and duly stamped in black and red–that any clerk of Oxford would be glad to have at the head of his couch.

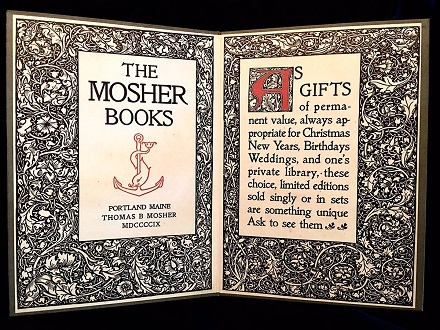

“The resurrectionist Mosher” his kinspirit Billy Reedy called him. Aye, how many exquisite things he disinterred, and how far ahead of the thundering herd to see the good things coming. In one of his crisp little prefaces he spoke of “that saving remnant who when they see a good thing know it for a fact at first sight.” As early as 1900 he was hailing the Irish literary renaissance in Yeats, Lionel Johnson, Moira O’Neill and others; and coming to the defence of vers libre. It was in those little grey-blue Bibelots, chance-encountered in college days, that Mistletoe first met Fiona Macleod, Francis Thompson, Synge, Baudelaire, H. W. Nevinson, William Watson, Arthur Upson, Richard Jefferies, Arthur Symons, Alexander Smith…. one could carry on the list ad lib. What was there in this hardy sea-bred uncolleged downeaster that made him open so many magic portholes? He had the pure genius of book-fancy; an uneducated man, as uneducated as Chaucer and Lamb and Conrad; and I like to think that when he took Aldus’s device for himself there was some memory of the time when an anchor meant more to him than an emblem printed on a title-page.

I like to think of the gook luck of the people who had the fun of learning in the Bibelot something of the extraordinary thrills that literature can give. I think it is not extravagant to say that as a collection of a certain kind of delicacies, this cargo of Mosher’s is unrivalled. I suppose it is the most sentimental omnibus that ever creaked through the cypress groves of Helicon. Like all men of robust, gamesome, and carnal taste, Mosher had a special taste for the divine melancholies of ink. Gently tweaked by subscribers for his penseroso strain, he replied “We shall prove that a humorous Bibelot is not, as we have been informed, out of our power to produce.” But, speaking from memory, I believe he exhumed only the somewhat Scollay Squareish hilarities of James Russell Lowell’s operetta about the fish-ball. Its title, Il Pesceballo, is the best of it.

I think indeed that a too skittish and sprightly Bibelot would have been out of the picture. Mosher’s sentiment was of the high and fiery kind, the surplus of some inward biology that made him the rare Elizabethan he is said to have been. He was by no means the indiscriminating all-swallower; his critical gusto was nipping and choice; in those brief prefaces you will find many a live irony, many a graceful and memorable phrase. The particular task that he set himself in the Bibelot was, moreover, not prone to casual mirth. He was the seeker among “spent fames and fallen lights.” the executor of unfulfilled renowns. The poets he loved were those who were “torches waved with fitful splendor over the gulfs of our blackness.”

Take it in beam and sheer, the Bibelot is an anatomy of melancholy. It has been called an encyclopedia of the literature of rapture, but it is that kind of rapture which is so charmingly indistinguishable from despair. Mosher loved the dark-robed Muse: he emprisoned [sic] her soft hand and let her rave; he fed deep upon her peerless eyes. He was the prince of editors: he did not come to his task until he had tried other ways of life and found them dusty. He was almost forty when he began publishing, and what did he begin with? Meredith’s “Modern Love!” Think of it, gentles [sic ?]. Would not that have looked like a lee shore to most bookmen in Portland, arida nutrix of publishers? But it was what he called the “precious minims” that interested him. There was in him more than the legal 1/2 of one per cent of Hippocrene. In 1895 he began his Bibelot and carried it through monthly numbers for twenty years. As editor he never obtruded himself. When he died I don’t think there was a newspaper in America that had a photo of him available in its files. He was the potential author of one of the most fascinating autobiographies that were never written.

So it was that there came to us, from what has been called the stern and hidebound coast, this most personal and luxurious of anthologies. These twenty little grey briquettes pile up into a monument. He was always, in the phrase he loved to apply to his favorite writers, “touched to finest issues.” He knew lapidary work when he saw it. Once he spotted a poem written by a contributor to the old Bowling Green. At once he wrote for permission to reprint it in his catalogue. “It is one of the few things,” he said, “that to me seem almost absolutely perfect.” May I tell you, without breach of manners, what it was? Life is very short anyhow for paying one’s respect to the things that need admiration. The poem was “Night” by William Rose Benét.

In these twenty volumes there is enough material even for those of us who never knew him to guess fairly closely into Mosher’s own tastes. He was all for “songs gotten of the immediate soul, instant from the vital fount of things.” And however sharp his taste for the fragile and lovely, there was surely a rich pulse of masculine blood in his choices. He was often accused of piracy. If it be piracy to take home a ragged waif of literature found lonely by the highway, to clothe her in the best you have and find her rich and generous friends–if this be piracy, then let any other publisher who has never ploitered a little in the Public Domain cast the first Stone and Kimball. The little upstairs fireside on Exchange Street, Portland, is one of the most honorable shrines that New England can offer to the beadsman of beauty.

They pile up, I repeat, into a monument that any man might envy, these twenty little fat books. No one reader will agree with all Mosher’s choices, but surely never did any editor of genius ramble with so happy an eye among the hedgeflowers of literature. A Scottish critic has said there is only one enduring test of a book: is it aromatic? These beautiful books, from beginning to end, are fresh with strange aroma and feed more senses than the eye. Words of Arthur Upson’s, printed here by Mosher, describe them:

Wine that was spilt in haste

- Arising in fumes more precious;

Garlands that fell forgot

- Rooting to wondrous bloom;

Youth that would flow to waste

- Pausing in pool-green valleys–

And passion that lasted not

- Surviving the voiceless tomb!

The Bibelot began and ended with selections from William Blake. And like Blake, Mosher gave us the end of a golden string.

Morley was an American journalist, essayist, and novelist.