Pottle, Frederick A. “Aldi Discipulus Americanus” in Amphora: A Second Collection. Portland, ME: Mosher Press, 1926., pp. 117-26. Reprinted from the Literary Review of the Evening Post. [December 29, 1923], p. 410.

Eight years ago, Thomas Bird Mosher placed opposite the little foreword with which he ended The Bibelot the first and last stanzas of one of Robert Frost’s most beautiful poems [see Index, Volume XXI]. I can think of no other words which would express more completely the thought which he would have chosen to stand at the end, not only of The Bibelot, but of his work as a whole:

Out through the fields and the woods

And over the walls I have wended;

I have climbed the hills of view

And looked at the world and descended;

I have come by the highway home

And lo, it is ended.

. . . . . . .Ah, when to the heart of a man

Seemed it ever less than a treason

To go with the drift of things,

To yield with a grace to reason

And bow and accept the end

Of a love or a season?

Thomas Bird Mosher, publisher of rare and limited editions of books in belles-lettres, died at his home in Portland, Maine, on August 31, 1923, at the age of seventy-one. I thought as I read the news story in the Portland Evening Express of another story Mr. Mosher once told me of a clerk in one of Portland’s largest hotels who told a Mosher enthusiast, who had come from afar in the hope of seeing the master personally, that he believed he had heard of a man named Mosher who carried on some kind of business in Portland, but that he thought he was dead. It is too true now. I imagine that the present citizens of Portland (the event of the story took place some years ago) barely noticed this news of the passing of their most illustrious citizen. Most of them had probably never heard of him. Part of the headline of the article in the Express reads, “Little Known Here Though His Works Were Widely Read in Foreign Countries.” If the Mayor or the Chief of Police had died, the papers would have given him most of the front page and arranged a civic memorial. But this man, whose name was known in San Francisco and London, in Bombay and Sydney, the publisher of the finest series of editions ever produced in America, and whose work as a whole surpasses anything since the days of the Kelmscott Press, slipped out of the life of their city without causing so much as a ripple of excitement. The truth is that he never really lived in Portland. He resided there almost continuously for over fifty years, and he published his books there from the same address for thirty-two, but he actually lived in a city of wider horizons. Portland was the place where he published his books, but he was not of it. In an unpretentious room on the second floor of a building on one of its lesser thoroughfares he breathed the air of a city which was the world.

I cannot believe that I shall never see him again. Truly, the happiest moments of my life have been spent in that room at 45 Exchange Street. You found the place the first time by the number. There was no sign which could be seen across the street; only a two-line legend on the jamb of the door stating that T. B. Mosher, publisher of fine books, had his office within. You opened the door and found yourself at the foot of a narrow and much worn staircase going straight up two flights. From above (in regions I never explored) came the peculiar grating and rolling sound of a press. You ascended the stairs and suddenly and unexpectedly found on the landing to your right a door with the announcement, “Thomas B. Mosher, Publisher.” You hesitated, wondering whether to knock or to enter boldly. The glass of the door was frosted so that you could not see in; you had no idea what to prepare yourself for; whether a large bare room with a press, or a little cubby-hole of an office, where you would find yourself confronting a busy and annoyed person across a large desk. You reflected that, at all events, Mr. Mosher could hardly be like that. You finally pushed the door timidly and it opened, rubbing at the bottom, making a sound like the press, which was still rolling and grating upstairs. Nothing happened. You waited a moment, your courage gone, and then a kind and genial voice called, “Come in!” You entered.

Oh, that room! The warmth, the dusk, the fragrance of it! Lighted on the front by windows opening over the street, but in the corners at the back dim with a mellow duskiness. . . Books all around you to a height easily reached from the floor. . . Facing you as you entered, a great fireplace of brick with blue plates on the mantel ledge, a fire of hard wood smoldering and glowing, the fragrance of maple smoke in the air. . . . In the centre of the room, facing the fireplace, a great comfortable davenport, and backed up to it a little bookcase with all the Mosher books. . . . Around the walls, small framed pictures of authors; you recognized Yeats, Swinburne, J. A. Symonds, an unusual Lincoln. . . . But, then from a desk by the window a man rose and came forward towards you, his hand extended in greeting. You knew at once that it was Mr. Mosher.

Those who own the full set of The Bibelot have an excellent portrait of Mr. Mosher as frontispiece to the index volume. It is the only one I have ever seen. If, like me, you did not meet Mr. Mosher until near the end of his life, you saw him as he appears in that photograph. A thick-set, rather portly figure, of middle height, dressed in a plain dark suit; a full, clear-skinned face, with nothing of a bookish pallor, brown hair (later quite white), thin and downy on top, but soft and abundant over the temples; a gray mustache, beautifully curling upwards at the ends; blue eyes with drooping lids and eyebrows going up at a quizzical angle. . . . You notice the passion of the full lips, the laughter in the quizzical eyes, the alertness, even youth of his bearing. He spoke to you again, you stammered something about his books, he laughed and pointed at the bookcase–and in a moment you were out of Portland and in his city of the world.

Oh, the afternoons I have spent in that magic place! Days when the fog hung heavy over the docks, and a gloomy drizzle washed the deserted cobbles of Exchange Street, shut in from the gray cold of out of doors, sitting on the great davenport before the quiet fire, reading or listening to that voice going on and on in its talk of books and authors. His voice (how can it be silent for ever?) was indescribable. It went with the laughter in the eyes and the lips; a quizzical, throaty voice with a velvet-soft rasp to it and a frequent chuckle–not a laugh; only a single note of amusement deep in the throat. “The Prophet says that the heart of mankind is desperately wicked.” I hear him say, “I think it would be better to say that the heart of mankind is desperately stupid.” A chuckle. “The reformers will never completely divorce genius from vice, I fear.” Another chuckle. “A dretful [sic] thing,” he would say of some unfortunate work of author or publisher; “A dretful thing.”

Those exquisite forewords which are the glory of the Mosher editions contain the passion and rapture of his talk, but they do not contain the humor, the sunny irony, the racy colloquial quality of his conversation. The gleam of his eye is there, but not the twinkle. We talked always of books. I do not remember that I ever asked him a direct question about his own life. But in the course of those magic afternoons, in chance allusions and broken sentences, I learned enough so that I could construct the general outlines of his history.

He was born in Biddeford in 1852. His father was the master of a sailing vessel. I never heard him say much about his father, but I can easily imagine him as a skipper of the old days; of Portland as it was when the boy Longfellow haunted the docks enthralled with

The Spanish sailors with bearded lips,

And the beauty and mystery of the ships,

And the magic of the sea.

The boy Mosher attended school for a few years in Biddeford and later in Boston. But at a very early age (before he was sixteen, certainly; I think before he was fifteen) his father took him out of school forever and carried him away to sea. I do not know the reason for this step, unconventional even in those days, but I have no doubt that it was because his father happened by a miracle to be a man of such unusual insight and sympathy that he was able to form a correct appreciation of his son’s peculiar talents. The boy was probably not doing especially well under the stifling routine of the public school, and his father had the courage to try a better method.

It may surprise those persons who think of education as solely the work of the schools to learn that Thomas Bird Mosher never went beyond the grammar grades. Yet what an education he built the foundation for on that clipper of his father’s as it ploughed its course through the seven seas! No critic or editor that America has produced ever had a more effective education in literature, if the work he did is to be taken as the test. He was never sorry for his lack of schooling; indeed, though he gave his sons a conventional education, he remained a frank and unconverted skeptic as to the values of mass education. “Having had little of school,” he once said, “it is no wonder that I loved literature.” When he left school to go to sea his favorite reading was the terrific romances of Sylvanus Cobb–The Smugglers of King’s Cove, Bion the Wanderer, etc.–and dime novels. He once told me that he left behind him a barrel completely filled with his dime novel library. “I wish I had that barrel now,” he added; “I have no doubt it would be worth a thousand dollars.” His father snatched him away from the public school, the trashy literature, the college education (“I am particularly grateful to my father for saving me from a college education,” he used to say) and left him for four years with the sea and one short shelfful of books–all good.

“No! I shall never again read books as I once read them in my early seafaring,” he wrote in one of those too rare personal essays of his printed in his miscellany, Amphora, “when all the world was young, when the days were of tropic splendor, and the long evenings were passed with my books in a lonely cabin dimly lighted by a primitive oil lamp, while the ship was ploughing through the boundless ocean on its weary course around Cape Horn.” What scenes, what visions, those casual allusions evoke for me! That slender lad, with passionate lips and eyes, leaning over the rail, gazing in a dream back along the white track of the vessel through the green calm, or lying on his back on the deck, with the snowy canvas billowing between him and the sun! What sights of foreign ports and strange people, what glimpses of land looming up beyond the bow after days and weeks of unbroken horizon, bringing the grateful tears into the eyes; what fury of tempest, what calm after the storm. . . . Why did I not talk to him of these things? Did he first read The Ancient Mariner out of sight of land? Did he stumble by chance upon Keats’s lines, and then read them again and again with a growing and incredulous rapture:

Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

One of the experiences of those years must have made an especially strong impression on him, for I remember hearing him mention it more than once. That was the time he sailed with his father into New Orleans with men for Gen. Butler’s garrison.

Four years of that glorious life of the sea, and then the days of his seafaring were over forever. I think he never again left this country except for one memorable trip to England, when he met York Powell (a man he held in especial reverence) and William Michael Rossetti. It may have been at that time that he first met William Sharp, whose Fiona Macleod writings he did so much to introduce. To those who know and marvel at the catholicity and range of his taste and the true scholarship of his work it seems incredible that he could read no language save English, and that, apart from those brief stops in foreign ports during his boyhood, he never visited any foreign country except England. I know that this was a great disappointment to him. I remember once, as I was looking at his edition of The Hollow Land, I told him how I once saw the Hollow Land itself. “It is as you come out of the Auvergnes and look down from the rim of the mountains upon the plain of Clermont Ferrand. Have you ever seen it?” I shall never forget the wistfulness of his tone as he said quietly: “I have never been in France.” Then he added, after a long pause: “And now I shall never go there.”

His four years of happy idleness were soon ended, and his circumstances demanded that he now make a way for himself. He was, I suppose, about eighteen when he began the struggle to make a living. And for the next twenty years he met with disappointment and failure. I can imagine him with the glory of those early years still upon him, his heart singing to the melodies of those immortal strains he had come to know so well, his eyes rapt with visions. . . . . What could he do? He knew only vaguely what he wanted to do, and no way to do it. I suppose he drifted irresolutely into connection with the publishing house he finally entered because of his fondness for books. His choice of occupation was no more his own than was Lamb’s. Like Lamb, he became a bookkeeper. But, unlike Lamb, he found a way of escape.

For twenty years he kept up that sort of thing. He left Portland for a year or two, only to come back to enter a newly formed partnership–a publishing business. “I had made a failure of everything else,” he said, “and I had to borrow money to go into business. The man who lent it to me thought he would lose it, but he lent it to me because he loved me.”

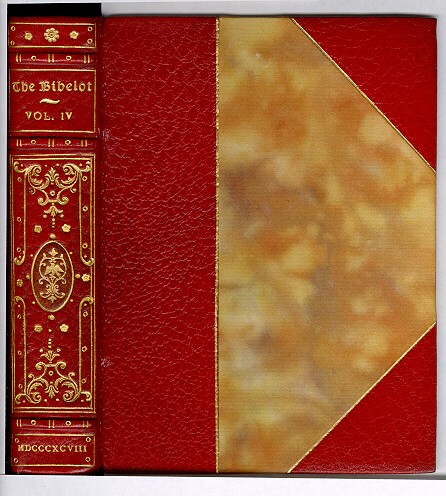

For eight years he worked with this firm, learning the practical details of publishing. All the while it was becoming clearer and clearer to him how he could do the thing he wished to do. He had held to that desire with unyielding tenacity. Through disaster and disappointment and failure he had clung to his dream of what he wanted. In October, 1891, when he was almost forty years old, and had, by his own admission, failed at everything else he had tried, he began the publishing of The Mosher Books. “Do what you know you would like to,” he said to me once. “You can’t succeed at anything else” His first book was George Meredith’s Modern Love.

As I ponder it I, who have not the courage of genius, wonder how he could have succeeded. Forty, a failure at business, with no regular schooling, and to begin with Modern Love! Why, of all the books he had to choose from, all the books he later published, did he choose that particular one? I am glad that I know. It was because the last line of that poem sequence expressed the idea which all his life had gripped him so mightily–the soul of The Mosher Books:

To throw that faint, thin line upon the shore!

Faint? Thin? I suppose so, for the circumference of the shore is large. But the line is there. No part of the world where English-speaking people live in any numbers is without those to whose feet it has borne its foam. It will delight the lovers of his work, I think, to know that, in accordance with his wish, the business will go on. No new titles will ever be added, but those books for which there is a call will be kept in print in exactly the form which he gave them.

Thomas Bird Mosher was the pioneer in the making of beautiful and inexpensive reprints of not-easily-accessible masterpieces of literature. To-day the advertising pages of our periodicals shriek with the proclamations of cheap classics. But all those who know The Mosher Books know that as he was a pioneer so was he always in a class by himself. Mere cheapness he abhorred. Expensive books he would not make. In choosing titles he was guided by only one principle: whether he loved the book or not. Every book he made a work of art, lavishing on it every attention to make it perfect in size and shape, in texture of paper, in type, in binding. And these exquisite things he sold for the price of ordinary books. He was, in these days of quantity production and cheap manufacture, a craftsman and an artist, a true disciple of Aldus, whose anchor and dolphins he placed upon his title pages.

Pottle was a professor of English at Yale University, and is widely known today as the editor of the Boswell books.