Needham, Wilbur. “An Attempt at Appreciation of a Rare Spirit” in The Mosher Books catalogue, 1923. Reprinted from the Chicago Evening Post, April 20, 1923, p.4.

( I )

He has done what every true booklover who is also a litterateur would like to do. He has done it so well that, like the work of the old masters, it is really not worth doing again. I think that the books of Thomas Bird Mosher,–books he never wrote but which are his because he has put upon them the imprint of his taste in book-craft and his selective genius in literary matters,–are meant for immortality. Some one is bound, after he has finished his work here, to take it up and spread broadcast the little volumes he has produced in small quantities for those who care. That will not matter, however, and it will come about naturally, easily.

( II )

For those who do not know Thomas Bird Mosher, I quote a few titles in the list of books which has been steadily growing since 1891: Odes, Sonnets and Lyrics of John Keats, the Daniel Press edition; The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft by George Gissing; Dreamthorp by Alexander Smith. Some were limited editions, or did not get a reprinting for one reason or another, and these are now out of print and very scarce. Others that I do not mention may be quite as unobtainable. The rest are reprinted whenever exhausted, in the same form usually as the original. There are more than three hundred titles in the list; and besides this Mr. Mosher has a set of books which he calls The Bibelot, a twenty volume collection of prose and poetry ranging from François Villon to Stephen Mallarmé, and from William Blake to Maurice Hewlett. His separate volumes are issued in series with charming names: The Brocade, the Old World, and the Venetian. One finds in many the name of Fiona Macleod; haunting titles like From the Hills of Dream and The Four White Swans.

Mr. Mosher, indeed, was among the first, if not the first, to discover William Sharp’s delicate things, and it was he who was practically responsible for the pen name that Sharp assumed for part of his work, Fiona Macleod.

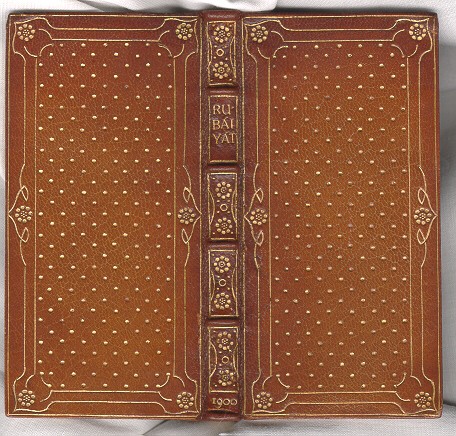

The format of every book is exactly in the spirit of the author–and in the Mosher spirit, too. Most of them, not to speak of leather bindings for those who do not fear the rot of years, are in old-style boards and in a cream cover of vellum, stamped in brown, and inclosed in a slip case to preserve from dust.

( III )

“The literary journals,” says Mr. Mosher, “are so full of details about works that sell by the carload that any attempt of mine would be like the needle in the haymow–‘lost to sight’ even if to memory dear! I shall hope to go on with my work, small as it is, however, until, to quote from another–‘the end is ended–the infinite begun’.”

There has been nothing quite like Thomas Bird Mosher before this day–he is not, he asserts, a “second William Morris”–and there will be, we suspect, nothing like him after this day is gone, and he with it.