Now… at beginning of this essay I know the reader must be saying to himself “here we go again, another story about another Mosher book in another binding—gads!” Very sorry to disappoint Mr. and Mrs./Ms. One-and-all, but this actually isn’t about a Mosher book, nor has it anything to do with ol’ Moshwig although I’m sure I’ll try to work in something along the way–you know me. Anyway, here are some reflections and thoughts prompted by a binding which sort of stole my heart, at least for the time being.

My wife, Sue, and I began collecting books with an “acorn & oak leaf” design around January 2009. It might seem like a brainless way to collect—sort of like gathering all red or green bindings and calling that a collection (as a bookshop clerk I remember the occasional customer asking for such which usually put a haughty but necessarily suppressed grin on my face and roll of my eyes). The month and year we started this is important because it’s when we both experienced a sharp downturn in our work. The economy was taking its nose dive in 2008 and at the beginning of 2009 we were faced with some of the same problems many other Americans were experiencing. I was unsure about how I might be able to continue collecting Mosher material (there now, I told you I’d somehow get him worked into the story!) and we were both reviewing how we could cut back on expenses while maintaining our critical demands for health insurance, mortgage payments, other insurances, and the like. So I proposed we jointly collect trade books with an “acorn and oak leaf” design since they were bound to be inexpensive.

Why acorns and oak leaves? The trees that majestically lord over our humble bungalow are mighty oaks. Each later summer and into the fall we fill wheelbarrows full of acorns we have to pick up, not to mention the 150 or so bags of leaves we collect thereafter for recycling. We could grumble about this, or we could take a cue from the martial arts and redirect the energy flow so as to mitigate its impact by glancing it to the wayside, or using the energy to redirect the assailant’s force so as to render it harmless. Instead of fighting the oak leaves and acorns, we began a kind of enculturation with them in mind, even to the point of celebration. Our Gordon-Van Tine bungalow was dubbed “Acorn Cottage” and we embarked upon a well considered plan to incorporate the “acorn & oak leaf” motif into our living space. Mind you, we don’t get carried away with this, but carefully weigh and consider each and every accompaniment to our interior quarters. In a nutshell, we decided not to fight ’em but join ’em and get some pleasure out of it.

The acorn & oak leaf collection is mostly made up of trade editions of British or American publications, and we only consider fine copies. Since we both have enjoyed the book designs of the 1890’s – 1930’s over the years, and since we both have numerous well designed bindings in our respective collections (Sue’s the Homes & Haunts of American Authors and mine the books associated with Mosher), we decided that this would be a perfect accompaniment to our home’s decorative furnishings which also give us the pleasure of having more books.

The collection has grown, in fact, I just added to it a few days ago with an English trade binding designed by Selwyn Image which I saw pictured in a special 1899-1900 winter issue of The Studio entitled “Modern Book-Bindings & Their Designers” (p. 7). Since most of these are trade bindings they don’t go for very much $$$ except for the occasional exception. We display them in a sectional bookcase and sometimes in stands on the fireplace mantle or elsewhere. In doing so, we unite a number of our loves: the love of the bungalow we now affectionately called “Acorn Cottage,” our love of nature and the oaks just outside our windows, our love of well designed books, and our love of integrating the outside with the inside as discussed by Claire E. Sawyers in her chapter “Marry the Inside to the Outside” in The Authentic Garden—Five Principles for Cultivating a Sense of Place (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2007). By adding books with the acorn & oak leaf design we just take this a step further.

All was happy. All was going according to plan. Then came along the unexpected –no, not an oak tree falling on our house. Something came up which altered our trade binding plan. Remember, there are exceptions. It was outside the trade binding realm and quite simply a fluke that I even came across it. While searching for some other items on eBay I happened upon the website of a bookseller who had leather bindings for sale and did a search for other things she might have when what to my wondrous eyes should appear? Not Santa nor his reindeer but something even better–a stunner. Not the Pre-Raphaelites’ term for a certain very attractive women, but in this case it’s a most likely product of a woman’s hands: an exquisite “acorn & oak leaf” designed binding from the late 19th or very early 20th century, a one-of-a-kind and a pricy one at that!

Not only does the book have the “oak leaf & acorn” design on the spine and front cover (book measures about 8″ x 5 1/2″ x 1 3/4″) but all page edges are stained a dull reddish-tinted brown with an overall gauffered pattern of gold acorns and dots. The binding is on the 1897 issue of the first trade edition of the William Morris title: The Water of the Wondrous Isles (preceded only by the Kelmscott edition of the same year). What can I say. We’re nuts! or maybe I should say: “we’re acorns!” Perhaps the most blatant example of the oak leaf and acorn design ever to be encountered, it’s a period piece in near fine condition. I don’t know why I even hesitated, but I asked Sue if she thought I was nuts (er, um, acorns) for even considering it. She didn’t hesitate for a second. “Get it” she said, and then proceeded to heap verbal praise upon it while examining the pictures. I called the bookseller and asked her a few questions about condition beyond what I was seeing in the photos. She indicated it was placed on consignment and she actually wanted to buy it for herself but couldn’t afford it. Indeed, she really didn’t want to sell it but I quickly egged her on to get her PayPal address to which I’d have to send the funds. Within ten minutes everything was concluded and she notified me that she received the payment-in-full and would be mailing the book the next morning. This initiated the long wait we all experience when we’ve landed something good for our collection. Tap, tap, tap, tap… check the calendar. It should be here today or maybe tomorrow at the latest. Certainly not beyond Saturday. Tap, tap, tap… What’s taking so long? Tap, tap, tap…

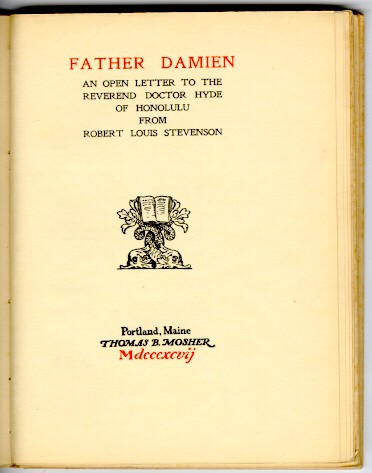

When I received the binding just before the weekend of July 4th, I closely examined it but could not find any name stamp or monogram; however, it seems as through the binder should be discoverable even without it. I mean, just look at that idiosyncratic lettering with each of those letters being individually constructed. It’s the American issue of the book (LeMire A-84-02) which lists New York first, then London in the title page’s imprint information. I thought just possibly the binding might be by an American, but then again the text could have been easily bought here in America and sent to England for binding which was quite common in those days. One of the keys to identification most certainly lies in the analysis of the binding’s elements.

It appears that the Morris book is bound in what the Guild of Women-Binders referred to as “Niger” leather, a goat-skin from the Niger Territories and introduced to England by the Earl of Scarbrough according to their literature. It was dyed by the natives with the bark of trees using some sort of secret process. In one of their advertisements, the Guild described it as “the only leather obtainable with that dull, rich, Venetian-red colour which simulates the tone of age.” Not only have I seen it on many a binding from the Guild of Women-Binders, but also on some of bindings I’ve seen by Douglas Cockerell. The leather is well suited for what one binder calls “carved and punched leather bindings” which I’ve also heard described as incised and modeled leather bindings.

I passed some photos by one of the ABAA’s bindings experts who immediately identified it as a binding from the Guild of Women-Binders (1898-1904), a collective name given to the loosely knit group of English women binders with headquarters at the bookseller’s shop of Frank Karslake of Charing Cross Road, London. In all fairness, however, it may also be by one of the binders of the Chiswick Art Workers Guild or even the Gentlewomen’s Guild of Handicrafts, both of which operated during roughly the same time. In addition to the more recognizable names like those of Annie MacDonald, Florence de Reims, or Constance Karslake, there were a myriad of unsung pupils who received training through the Guilds and any one of these trainees could have been responsible for this binding.

More specifically, there are a number of reasons why this binding is identifiable as from, or at least somehow related to, one of the Guilds listed above. This binding exhibits characteristics that Marianne Tidcombe discusses and illustrates in her Women Bookbinders: 1880-1920 (Oak Knoll Press & the British Library, 1996, particularly pp. 115-130). Chief among these is that (1) the type of leather used which I presented earlier, (2) many of these women binders employed a field of gold dots behind their designs, (3) their early work often used modeled leather bindings, (4) their amateur binding designs tended to be a good bit more free in design when compared to the professional book designers of the era, (5) early on member of the Guild of Women-Binders tended to use rather drab endpapers and scant treatment of the leather turn-ins inside the covers, or so it is with the examples I’ve seen including those in my own collection, (6) and it was a prevalent practice for the lettering to be formed using gouges and short line tools or dots often making for some eccentric letter forms. Furthermore, the fuller identification of this binding might well hinge on its particular letter tooling, most notably the “W’s” of “Water” and “Wondrous” as exemplified on both the front cover and the spine.

That’s where I’m at for the moment. I’ve checked through many volumes containing pictures of this era’s bindings and thus far have not encountered the same lettering much less the binding itself, although there are many examples which are closely related and which are by the Guild of Women-Binders or the Chiswick Art Workers Guild. I may never get beyond its general attribution, but maybe someone might be able to precisely identify the binder herself. What I can say, unqualifiedly, is that such a binding resonates with me and my wife. It’s hard to put one’s finger on, but it leaves a lasting impression of the spirit of the Arts & Crafts period and of William Morris and others who led the quiet revolution in printing and design that helped to inspire thousands. Of course many millions never cared then nor do they care now, but one has to hang one’s hat where one’s proclivities and sympathies lie. To each his own, but for Sue and me tapping into the ongoing spirit of these folks makes the difference between a life just lived or a life lived well. And so the binding takes its place in our expanding acorn & oak leaf design collection which helps to enhance our own experience and sense of meaning here at Acorn Cottage. I wonder if the creator of this binding ever envisioned its importance to her fellow beings of a later generation.

Philip R. Bishop

July 8, 2010

This article is Copyright © by Philip R. Bishop. Permission to reproduce the above article has been granted by Gordon Pfeiffer of the Delaware Bibliophiles and editor of that organization’s newsletter, Endpapers, in which the article appeared in the September 2010 issue. No portion of this article may be reproduced or redistributed without expressed written permission from both parties.